It's been a while since wrote something here and this will surely be my first post about something that is not a live review or some interview.

I wanted to start this topic earlier as I was always interested to know how strong influence any kind of music has in war zones. To me personally that will always be fascinating. First of all because I'm one those persons who survived the most horrific war in Europe after the Second World War and second, I could never really imagine earlier that people who live in war zones can actually think of listening or playing music while their main concern is how to survive the whole shit out there.

I've talked to many friends of mine who're at least 10 years older than me and listening to their stories of escaping from reality really touched me because I was only 2 years and 3 months old when everything began.

GNU, Eternal Remembrance, D.Throne, Neon Knights were just one of the few ones who played metal music in a period of war ('92 - '95) and they were not the only ones who have given people some hours of mental relaxation. Many people would hardly believe this but there were some guys who were really, really brave to come to play a show in Bosnia despite the fact that they could die and never see their family and friends again. These guys were Bruce Dickinson of Iron Maiden, Chris Dale, Alex Dickson, Roland Hyams, Alex Sponder Elena, Andy Veasey and if I forgot someone here, you'll surely be more informed in the following column, originally written by Chris Dale (and previously in 3 parts) on Metaltalk this summer.

So make yourself comfortable and bring yourself a coffee/tea/beer or what else you prefer cuz this will be a long journey :-)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Back when I was in Bruce Dickinson's band, I woke up way too early one day with the phone ringing. It was Bruce.

"Morning!" he said chirpily. I looked through the curtains. He was right.

"Yeah, morning!" I agreed.

"We've got another gig come in," he said.

"Great news," I replied. I love doing gigs.

"It's Sarajevo," he said. This was back in 1994 and even in my blurred mind alarms bells started ringing.

"Aren't they having a war?" I asked.

"Yeah, sort of... but it's all good. We're under UN protection and we might get a go in a tank!" he enthused. "Are you up for it?"

"Errr.... OK then," I tailed off. It was like interrogation under sleep depravation. I'd have said anything to go back to bed right then and besides, I had always wanted a go in a tank.

|

| Yours truly at Split Airport |

When I woke up properly a bit later I thought about the strange conversation. Apparently it wasn't a dream. We were going to do a gig in war-torn Bosnia.

But it hadn't been in the news for a while and surely Bruce wouldn't be going anywhere properly dangerous. He's far from stupid. Most likely the war must have quietened down since the UN peacekeeping force had arrived... or so I thought.

As a bit of background, in the early 1990s the former Serb dominated Yugoslavia slipped into a series of vicious civil wars. Firstly Slovenia broke away from the republic, then a short war with Serbia ensued before Croatia also broke away. Croatia was the second largest (next to Serbia) of the nations of the former Yugoslavia and with a hastily formed army they put up a fierce defence of their new freedom from Serb domination.

Next Bosnia declared independence. Bosnia was in a more difficult position with Serb minorities in the North and East and Croat minorities in the West. The Bosnian Muslims lived mostly in the centre but the divisions between the communities were not clearly defined by borders. All three nationalities lived next door to each other in many towns and all three now turned on each other.

These were especially ruthless wars. No quarter was given to men, women or children. Mass murder, mutilation, torture and organised rape were common. All sides were guilty of atrocities but the Serbs were the perpetrators of some of the worst and on by far the largest scale.

Finally the UN sent in a peacekeeping force to untangle the three warring factions and impose a truce. A no fly zone was enforced, Sarajevo was still under siege but things seemed to have calmed down, at least on the news... or maybe the continued slaughter was simply no longer newsworthy?

So a couple of weeks after the initial call, we're getting ready to fly to Sarajevo. There were no direct flights (that should have rung more alarm bells), so we were flying to Split in Croatia from Birmingham International. Regular flight from a regular airport, it's all fine so far...

Just when we got on the plane it occurred to us, perhaps for the first time, that this might not really be alright. The plane was full of British soldiers, there were no holiday makers there. We were the only long haired civilians on board. Everyone else on this plane was going to a war. Oooops!

When we landed at Split airport we were met by Colonel Stuart Green, a British Army officer who was very friendly, full of smiles and lots of hand shaking.

Alex Dickson, Bruce Dickinson and myself at Split Airport

"Thank you so much for coming out here, really so jolly good of you," he gushed. "But you've had a wasted journey, I'm very sorry to say. The show's off, it's all gone a bit hairy out there. We can't guarantee you safe passage into Sarajevo anymore so I'll get you on the next flight back. But really thank you so much for coming this far".

Several of us perked up at this news. Oh, well, nice day out, let's have a sandwich and pop home. But not Bruce. He wanted to know more. How bad was it? Could the mission be rescued? Was there another way we could get through?

I should probably at this point tell you who "we" were. There were eight of us.

|

| Our gang from left to right: Jed front of house engineer, Andy Veasey bass and drum tech, Alex "Sponder" Elena on drums, Bruce Dickinson- you know him already, Bob Edwards guitar tech, Alex Dickson guitarist and Roland Hyams, press agent. |

Bruce, he's the lead singer of Iron Maiden. We're in the middle of touring his 'Balls To Picasso' solo album. He's also the instigator of this whole scenario and his enthusiasm for it knows no bounds.

Alex Dickson, he's our guitar hero. He generally prefers guitars to wars.

Alex Elena, we called him Sponder to avoid/create confusion. He's the drummer and he plays very loud. He's also Italian I should warn you, and like most of his countrymen (and sensible people all around the world) believes good food should have priority over bloodshed.

Sponder and me at Split Airport

I'm going to be expected to play bass at some point.

Roland Hyams was our press agent and he was coming along to report on events, liaise with folk and handily keep a diary (to which I've frequently referred in telling this tale). We absolutely relied on him to keep our spirits up on several occasions.

We had a small road crew with us. Irish Jed was going to be doing our front of house sound (that is if they had a sound system at the gig, we still didn't know for sure what was going to happen at the venue).

Bob Edwards was Alex's guitar technician. Bob had put himself firmly in the pacifist camp when on tour one day he had failed to fix the screaming feedback in Alex's amp but instead had concentrated on building an impressive floral display on stage left.

Andy Veasey was our super-tech looking after Sponder's drums and my bass. Me and Andy were mates from back in Wales, a top bloke. He was the one person in this scenario that I looked to for common sense on all occasions.

"We should take their advice and go home," he said solemnly.

But as luck would have it, Bruce had met some folk from a charity group called The Serious Road Trip. They did amazing work. They were mostly foreigners (Brits, Aussies and Kiwis) and they drove truck loads of supplies into worn torn areas then performed circus routines for the local children.

They painted all their trucks in bright yellow with cartoon characters on the sides at a time when every other vehicle on the road was in dark green camouflage. They were doing such a saintly task but worryingly for me, they were all quite clearly insane. They'd take us through, they said.

Me with some Serious Road Trip crew at Split Airport

We arranged to go for dinner with the British Army then meet up later with the ironically named Serious Road Trip.

Dinner was in the UN Other Ranks canteen in Split. It was over-cooked roast beef and veg, just like school dinners but bigger portions. It was great.

A misunderstanding in translation at the UN base in Split

After dinner we had a briefing from Squadron Leader Dave Tisdale, an RAF officer. He took us to a lecture room on camp with a big map of Bosnia on the wall. It had brightly coloured star stickers all over parts of it.

He gave us a background as to the war, showed us the route we'd be taking and told us that until recently they'd contained most of the small in-fighting. Did we have any questions?

I had quite a few actually.

"What are the stars for?" I asked innocently.

"Yes, I thought someone might ask that. As I said until recently we were getting a bit quieter. The stars are fire fights we've had reported today. There's been a quite a few as you can see..." He looked at the very starry map. So did we.

Then we went over to the Serious Road Trip centre. It was a hippy camp in the hills. They were very hospitable and plied us with beer and more food. They were very dedicated to their work in bringing a glimmer of light and fun to Bosnia's suffering children.

Bruce and our Serious Road Trip Driver at Split Airport

They showed us video footage of them juggling in clown make up for shell-shocked kids. They took orphans for a day at the beach. We were humbled.

The video showed their trucks driving through villages shattered by artillery barrages. One video showed a truck driving along before a shell struck just in front on it. The truck swerved and avoided the falling debris. We were shocked.

Now it was dark we could hear occasional small arms fire in the distance. This was the best time to set off they reckoned. We'd be less visible, that's what they said.

I don't think it was only me among us now that was doubting the wisdom of their bright yellow colour scheme. Our truck had Road Runner painted on it too.

Perhaps the beers we'd consumed made us temporarily think this was all going to be fine still, so we got in the ex-military truck. The night was freezing cold.

Most, including Bruce, were in the back. There were no seats so everyone just sat on bits of supplies with a case of beer between them. I volunteered with Bob Edwards to sit up front for the first shift with Dave, the driver.

He was a young New Zealander, very keen, very alert. He crashed the gears, made the most of momentum and never slowed down. The scenery was pitch black except for the dimmed headlights. There were very few street lights; even most towns we passed were in ominous darkness.

Sometimes we drove down proper roads, sometimes roughly hewn tracks on the side of mountains with a cliff drop on one side. At all times we drove full pelt.

Dave told us its best not to go slow as we'd be more likely to be ambushed. As well as three warring armies, bandits would also stop vehicles for their contents. Everyone in the country was armed and hungry.

We stopped once to re-fuel and for a pee. When we jumped down most of us instinctively went to the side of the road to relieve ourselves but Dave called us gently back to the middle of the road.

"Don't go in the hedges, they're sometimes mined. The one lot drop a shell on the road, the other lot jump into the hedge for cover and find the landmines. Besides you don't know who's in the hedge".

From then on we just peed out the back of the moving truck or in an empty bottle if needed. Nobody asked for another stop.

We did however stop a couple of times for passport checks at UN checkpoints, one manned by Spanish soldiers, one by Slovaks.

"Hola," I said to the Spanish soldiers. They ignored me and we drove off.

"Do you speak any Serbo-Croat?" Dave asked me.

"Da, ja govorim malo srpsko-hrvatski," I said slowly, pleased with my homework.

"When we stop at the local army checkpoints later, don't speak any Serbo-Croat to them. Ever. No eye contact. You don't want to get into conversation with them, you don't need to make friends. Most of them are constantly drunk too, on Slivovic. We just keep quiet and speak when we're spoken to."

He looked a little nervous. I took his advice quite seriously now. This wasn't a game, was it?

We drove on through the night and just as day was breaking and I'd nodded off a little for the first time, we pulled up on the side of Mount Igman and saw Sarajevo lying in the valley below us. But the scene wasn't as beautiful as we'd hoped... Read more about the Serious Road Trip's work at http://www.theseriousroadtrip.org/history/

Major Morris and our Serious Road Trip Truck on the outskirts of Sarajevo

Daylight revealed that many of the buildings we'd passed had been riddled with shell and bullet holes. We were now among a small grouping of partially demolished houses at a Bosnian Army checkpoint. Soldiers and civilians shuffled around in the mud looking exhausted. There had been fighting here last night.

This is where we were being met by the UN.

While we waited, Bruce signed a photo for some Bosnian soldiers and him, Roland and Bob shared the last of the vodka from the truck with them and some locals in an old cabin.

The Bosnian soldiers were mostly scruffily dressed in khaki green, wrapped up against the cold as a mild snow had settled here overnight. One of them, a teenager with a Kalashnikov, sniffed at our half emptied case of beer.

"Piva!" he shouted and his eyes lit up. I shook my head at him (trying to follow the earlier advice of not to speak) and looked the other way. Luckily he shrugged and sauntered off. I wasn't going to argue with an armed child for half a case of beer. It was his if he'd insisted.

Loading the Armoured Personnel Carrier at the second Bosnian Army Checkpoint

Meanwhile we'd been met by Major Martin Morris (who'd organised this whole event) and a pair of UN armoured personnel carriers. An armoured personnel carrier, or APC, is a bit like a tank but without a turret and with a bit of seating room inside.

An NBC television crew turned up to record our arrival but caused instant offence to the Bosnian army by filming at the checkpoint.

We were told that taking photographs in a war zone was not a good idea, especially if any of the subjects could be identifiable military targets. As you can see from this feature, we didn't take that advice particularly seriously at the time.

Andy and Bob got our guitars, drums and amps in one APC and we mostly squeezed in the back of the other for the journey into Sarajevo itself. This was quite exciting. Bruce was right. We were going in a tank after all!

Sponder had borrowed a Kevlar helmet and was looking out of the open top of the APC. I had a peak too but a soldier inside called me to sit down.

A view out the top of our APC with a Danish armoured car escorting us

"I wouldn't poke my head out there without a helmet if I were you" he said earnestly. "They (the Serbs) sometimes snipe around here. They're watching us all the time. Never forget that."

I instantly lost all interest in looking outside, not least because the view of rows of burnt vehicles and shelled out houses with civilians huddled over open fires in them did nothing to cheer me up. I chatted to the British soldier instead.

"I read in the papers," I started curiously, "that the British army has killed 16 Croatian soldiers and 32 Serbs out here".

He laughed "Yeah, and the rest. Those will probably be the reported ones. The thing is when we get fired on we have to identify a target before firing back according to the rulebook. Then when we've disabled the target we have to go up into the hills to confirm it before reporting the incident."

"Personally, after emptying a magazine into a hillside the last thing I want to do is check up there to see how the guy on the receiving end is getting on, let alone his mates."

That wasn't quite what the Telegraph had reported. I asked him generally how it was going keeping three sides apart.

"Three? No, there's four warring parties here with us trying to calm it down in the middle. The Serbs, Bosnians, Croats and the French."

He's got muddled up, I thought, "But aren't the French part of the UN peacekeeping force?"

"You tell them that," was his answer. "Everyone else is held back by all this UN red tape but the French are on the offensive. They're not messing about here. They took the airport by storm."

It was through the airport area that we travelled, one small link between Bosnian and UN (or in this case French) territory that the Serbs did not command.

I know the French got a lot of international criticism for not taking part in the more recent Iraq war but there's little doubting when they do go into action they play to win.

Another soldier I later met told me that at one point in the Yugoslav Wars, the Serbs had kidnapped a few French troops to hold for ransom or to use as human shields.

Rather than negotiate, the French immediately armed and scrambled a helicopter squadron from France without waiting for UN approval. They were already en route when the Serbs wisely released their prisoners. That wasn't in the papers either.

And besides, the French were going to prove very useful to us later in the story. Anyway, I'm getting ahead of myself here...

A typical house on the outskirts of Sarajevo

We went in our APC to a UN base in the city centre for a welcome breakfast of... bread and butter with some black coffee. Nothing else. Everything was in short supply and even the UN were on strict rations here.

But we didn't care about the lack of variety, we were hungry, it was lovely and we stuffed ourselves. Then we were straight off to the venue to unload the gear for the gig, while Bruce and Roland went off to do press with Reuters, NBC and a local radio station (Wall Radio, I think they were called).

I've seen a lot of load-ins in my time but this was the only one I'd seen from an armoured personnel carrier, so me and Alex Dickson stood around in the street to watch in interest as the tracked beast reversed up to the loading doors.

There was a British soldier fully armed and in kevlar armour watching with us. He was a friendly type and pointed out some local sights of curiosity.

"See that horizontal brown line up on the hillside over there?" he gestured up into the distance, "with that white, blue and red flag flying?"

"Oh yeah," we'd spotted it.

"That's the Serbian frontline trenches. They're always watching. They're watching us now. They sometimes snipe down into this street. If I were you..." We didn't hear the end of his sentence. We were already inside.

The whole city lived under this state of siege, with the ill-equipped Bosnian army inside defending its half demolished capital and the stronger Serbian army surrounding, sometimes letting vehicles and supplies in, sometimes not. Sometimes they sniped at Bosnian civilians queuing for food or water, sometimes they fired an artillery shell or two into town. Some days were better than others, and some days were worse.

This had gone on for years. The siege officially lasted from April 1992-Feburary 1996. We played there in December 1994. It was the longest siege in modern military history, three times longer than Stalingrad.

In 2003 the prosecution at the trial of the Serbian Major-General Stanislav Galic described the Siege of Sarajevo as "an episode of such notoriety... that one must go back to World War II to find a parallel in European history."

"Not since then had a professional army conducted a campaign of unrelenting violence against the inhabitants of a European city so as to reduce them to a state of medieval deprivation in which they were in constant fear of death... There was nowhere safe for a Sarajevan, not at home, at school (nor) in a hospital from deliberate attack."

But inside the venue and seemingly away from the war outside, the gig was a normal mid-size theatre venue. The Bosnian Culture Centre it was called.

There was a sound system (of sorts), a good size stage and some lights. Three lights. More might be coming later they said. Not all of it was in working order but nothing worse than you see on an average peacetime day in Spain.

"Nema problema", the locals said. They worryingly said that everytime a situation looked unwise or dangerous.

Our crew of Jed, Andy and Bob worked hard to make it functional. Some stuff needed fixing. Some could have done with replacing but with a siege on recently the locals had had other things on their minds and besides they hadn't been able to get new parts for a while.

During the afternoon a few of the owners of some parts of the PA system tried to re-negotiate for more money than they'd previously agreed. This was all being done in good old reliable German Marks, the only currency worth anything out there. At one point it looked like the show might be off. But Major Morris, Bruce and Roland argued with the owners, promises were made and the show was back on.

We were later told that this was standard practice here and was how business on all levels was done, from haggling over food in the marketplace to negotiating a truce between the warring parties. First you make an agreement, then you change your mind and demand more.

It turned out that the PA, lights and other production costs were to be made at the bar that night and nobody was getting paid until a bar profit was made.

The problem being that there was no beer. Everything now relied on a promise of a last minute delivery by Danish UN troops trying to get through Serb lines.

In the meantime (and blissfully unaware that anything was wrong) we went ahead and soundchecked. It was loud and heavy. The system wasn't brilliant but this was going to be a great gig after all!

If the Danes got through...

After soundcheck I went backstage to relax, have a nibble and change my bass strings. Yum, there were chicken nuggets! I tucked in. One of the guys from one of the local support bands looked over.

"Can I have one?" he pointed at the nuggets.

"Yeah, sure" I said. He ate slowly, looking at it and savouring the flavour. Then he told me he hadn't seen chicken for two years.

They had eaten almost all the poultry in the city soon after the siege had started. This must be frozen UN supplies brought to the venue especially for us. He eyed up the spam pizza...

"Help yourself." I offered him my old bass strings, I'd only done a couple of gigs on them, they were still quite fresh if he wanted them. He was keen to have them.

Then, I realised if they hadn't had much chicken for two years they probably hadn't had any bass strings at all in town. One of the ironies of the music industry is that if your band is doing well and making money you get given free strings, but if your band is skint you have to pay for them.

If you're under siege you can't even pay for them. I gave him all the strings I had in my case, telling him to give them to other bands too. Both Alex's did the same with their drum sticks and guitar strings.

He asked if I had any drugs. Cocaine or heroin maybe?

"No" I said "Drugs are bad, m'kay?" (except South Park hadn't been invented then, so I probably said something equally patronising).

He told me heroin wouldn't shorten his life expectancy. He was conscripted into the Bosnian army defending the city. Both the support bands were.

"I do three days at the frontline, then two days rehearsing with the band, then three days at the front again. When I first joined the army all my friends got killed, so I got promoted."

"Now I watch and shoot while the younger soldiers push forward and then they get killed. I shot an old woman once. I just saw something move in the hedge and shot it. I saw her fall. Then I had a nervous breakdown and spent a while in the hospital."

"But I'm back at the front now. I will get killed one day. Do you think heroin would harm me?"

He was in real life, very real life. Live every day like its your last, people say. This guy was doing that because, quite literally, he might die later this week. I was a tourist eating processed chicken here, flying home soon. He wasn't leaving.

He fought and he played guitar. Nothing else. I arsed around a lot and played guitar a little bit. It suddenly seemed quite trivial what I did.

Meanwhile the Danes had made it through with the beer delivery. Gud bevare Danmark! The bar was stocked and the doors could open.

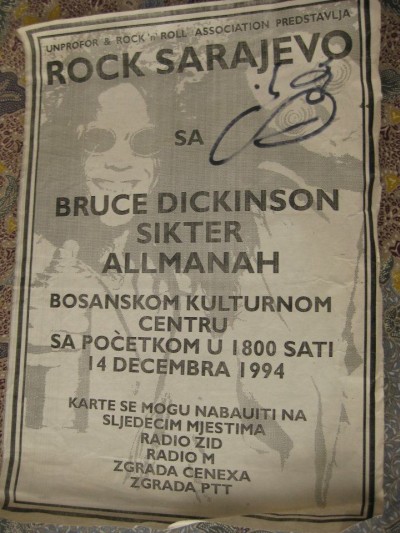

Support bands, Sikter and Allmanah did their shows. They were both good and they rocked like their lives depended on it. The audience loved them and they bathed in the spotlight.

Poster for the show

Then we did our gig. Unlike many 'for the troops' gigs in war zones, we were playing 'for the people'. This is what Major Morris had planned - the people of Sarajevo got a night out at a Heavy Metal gig in the middle of their personal hell.

There were also some UN soldiers there and some Bosnian army soldiers too. They deserved a night off as much as anyone.

We were the only foreign rock band to play in Sarajevo during the siege. Joan Baez was the only other foreign artist to perform there in the four years.

We played pretty much the set you hear on the Bruce Dickinson 'Alive In Studio A' album. The audience didn't know the songs (if they couldn't get chicken or bass strings, they probably couldn't get the latest Heavy Metal releases either). But we could have done anything up there and we would have got the same reaction.

Scream for me Sarajevo!

"Scream for me Sarajevo!" called Bruce, and they screamed for him. They screamed in a hysterical Beatles style all the way through. It was a release for them. It didn't matter what we did, they just screamed.

Major Morris played air guitar off to the side of stage. I didn't realise army majors did that kind of thing but apparently they do.

Alex Dickson shredding for the kids

The show finished quite early. There was a very strict 10.00pm curfew all over town enforced by the Bosnian military police.

After the show we had a quick few drinks with the locals and some UN soldiers. I got chatting with another British squaddie. He had a lot of respect for us.

"We never thought you lot would come out here in the first place then after this afternoon, we thought you'd be straight out!" he was laughing to himself, over what seemed to be a very private joke.

"Why, what happened this afternoon?" I asked, my innocence getting me further into trouble each time I opened my mouth.

"You know, when they shelled this place earlier?" he said, amused.

"No?" I said. He told me that the Serbs had fired two mortar rounds at the front of the venue this afternoon. They didn't want to kill us as that wouldn't look good on them (not just the bad international press but they probably had a fair few Maiden fans in their own army too). They just wanted to scare us off. They simply didn't want the people of Sarajevo to have a night of rock.

We'd honestly missed the shellfire. Our soundcheck was very loud after all. We have our soundman, Jed to thank for that.

Later we went back to the relative safety of the UN base in town. We'd been given a couple of dormitories in what may have been a former school or large office building. The windows were sandbagged halfway up, the rest was covered in black plastic.

"It stops snipers watching you" we were reassuringly told. Even so there was a dated bullet hole next to my bunk.

The bullet hole in the wall next to my bed

Our next problem was a logistical one. We had a couple of bottles of reasonable red wine from the gig but we had no glasses or cups at all. We're stuck in a school dormitory, on a UN base, after quite a full-on day, with the vino just looking at us. Who would have a bottle opener and wine glasses here?

I knew... the French!

As sure as they'd brought armour piercing rounds, they'd have brought wine glasses. Me and Sponder were off on a mission to find the French Officers' Mess.

Along the way we found more reassurance in the form of posters like this one about spotting different types of landmines.

Posters in the UN Base at Sarajevo

After getting lost a couple of times we eventually knocked on the French Officer's Mess door.

"Entrez", I heard from inside.

We stepped in I and introduced myself in my best schoolboy French, "Bonsoir, nous sommes les musiciens qui avez jouons dans la..." I knew it was all sounding wrong in my head.

"Yes, we know 'oo you are" said the nearest officer in heavily accented English while lounging back in his chair with a cigarette.

There were about half a dozen of them all in combats, eyeing us with suspicion.

"We were wondering if we could borrow eight wine glasses, si'l vous plâit? And a bottle opener?" He almost grinned for a second but thought better of it and merely raised an eyebrow instead and got up to fetch them from a cupboard opposite him.

"We'll bring them back," I said.

"No, we will get 'zem from you," he said helpfully but quite firmly. He looked a bit like Clouseau too.

"We're in the next block, if you go up the stairs by the..." I offered.

"We know whe' you are," he said closing the door behind us in the same helpful but firm manner.

Where would we have been without the French? Vive la France! We drank and were merry, then settled down to sleep. Job done!

Sponder asleep next to the sandbagged window

Tomorrow was a relaxing day off in Sarajevo, then hometime the day after. This wasn't so bad after all, was it?

I laid back in my bunk still dressed (it was freezing cold), pulled the blanket over me and closed my eyes. As I drifted in and out of sleep, punctuated by distant gunfire, I wondered what there was to do on a day off here. As with everything else in a war zone, I found it was done very differently from anywhere else I'd been before...

|

| Your Humble Narrator |

So, what do we do on a day off in Sarajevo? Well, much the same as we'd do in any other town.

On days off on normal tours you might do some sight seeing, maybe do a celebrity appearance or signing session type thing for some fans, then go to a bar or find a party.

All three of these happened in Sarajevo but being in a war zone they were all a bit more surreal than on 'normal' tours.

Being shown the sights in Sarajevo was done by Major Martin Morris and a couple of British soldiers in a mini-bus, driving along mostly deserted streets through the ruins of what had been a modern thriving city. Every other building was pock marked by shrapnel. Most of the windows were long gone and now boarded up.

|

| A street scene in Sarajevo. Notice the missing windows and the wrecked bus with sheet metal down the side to protect its passengers. |

Spare bits of greenery were converted to vegetable patches, even the roadsides and central reservations. But the growers risked death by sniper fire every time they checked on their carrots.

We stopped here and there to see the sights. As I remember these sights consisted mostly of views of the Serbian frontlines (always from a distance) and various shell holes (usually in civilian targets such as a block of flats or a market place).

We saw a large graveyard with all of the graves looking poignantly fresh. Each time we got out to see the sights we rushed back inside the mini-bus, as if its thin panels offered real protection. We kept our heads low through fear. This was not a fun-filled tourist trip.

Our 'celebrity' personal appearance was a little different too. Bruce and Alex were going to do an acoustic session at an orphanage.

An orphanage is always a kind of sad place, kids who for whatever reason don't have their mums and dads there to look after them. This was more tragic.

These kids had all lost their parents in the war. Many of them had seen them murdered in front of them. Some were still in shock, just staring straight ahead. They'd been like that for months. Others clung to us and wouldn't let go. Maybe they knew we'd be getting out of here soon.

Alex Elena playing with a child at the Orphanage

There were two shell holes in the playground. The people running the orphanage told us the Serbs had fired the first shell during playtime. Then they put the second one in when the ambulance crew arrived. It was a cold attack and was calculated to cause the most possible casualties amongst children and non-combatants.

It was under these conditions that Sarajevo lived. Before we got there I had known this was a war. I had known that wars are bad things. But I wasn't emotionally prepared for this at all.

In the evening we went to a local fire station, where UN firemen and other workers were having a small party for us. I'm not sure what the real address was but it was known to our British Army hosts as 'Sniper Alley'. I resisted asking how it got its name.

It was a dual carriageway that was largely deserted as dusk approached. There were burnt out cars and rubble across the road and its pavements.

The sensible route to take, we were told, was just blasting down it at full pelt while also swerving left and right. I've been in cars before when people drive too fast, sometimes because they're drunk or stupid, often a combination of the two. Somehow it's even scarier when a sensible and sober driver does it deliberately because dangerous driving is infinitely safer than safe driving in this topsy-turvy world.

I didn't actually urinate myself on the journey but I seem to remember it was a close call.

At the fire station, Andy and Bob set some of our gear up for a quiet jam. We didn't bring Ampegs and Marshalls down here so one of the locals was going out to pick up a little guitar amp from his friend's house. Sponder went with them out of curiosity.

When he got back he told us that at the friend's house, all the family were in one room with a nine-volt battery running a single Christmas tree light bulb taped to a mirror to illuminate the room. They invited him in and offered him food and drink.

We felt unable to help these people. Sponder gave this household all the British money he had on him. They cried in gratitude but nothing could help them really. Back home we had lit houses, CD players, nights out and what we took most for granted, relative personal safety.

These people had none of that. They all had crippled, missing or dead relatives. They lived in squalor and fear.

Yet, you know the odd thing? They were, more alive, more happy for the moment and more generous with what little they had than anyone back home. Their human spirit was unbroken.

These people smiled. They were probably not far from clinical starvation and yet they offered Sponder food. All the civilians we met out there were like that.

During the gig the night before, people at the front had a few times rolled cans of beer across the stage at me. I thanked them and gave them back. We had free beer backstage (thanks to the Danish Army!). These people had no proper running economy. Half of them had no regular water supply but they would buy you a beer.

Alex Dickson and Bruce performing an acoustic 'Tears Of The Dragon' in the fire station

Back at the fire station Bruce and Alex did a few acoustic tunes, then me, Sponder and Alex jammed around a bit and got some of the locals up. One was the Portuguese UN Medical Officer - he wasn't a bad drummer! We did 'Jumping Jack Flash' with him.

The insane situation outside broke down all barriers, smiles and beer flowed all round till late in the night... or would have done if the Bosnian military police hadn't turned up to enforce the curfew and send us back to base.

Jose, the Portuguese Medical Officer on drums!

The next morning after an emergency rations breakfast of pasta and baked beans Major Morris and our British Army friends from the previous days were ready to pick us up for the trip out of the city. They were driving us to a UN base in Kiseljak, where we'd get helicoptered back to Split and flown home from there.

The only slight worry we had in advance was that we'd be passing through Serbian Army lines this way.

We were neutral non-combatants in the war and we were being chaperoned by British UN peacekeeping soldiers in armoured Land Rovers. The UN had arranged with the Serbian command that we were coming through so nothing should go wrong for us but anytime you have to meet a group of armed and drunken murderers is cause for concern.

Also the thought of actually meeting the people who had been deliberately putting Sarajevo in such a state of death and misery was daunting in itself.

We were due to pass through four Serbian checkpoints. They were imaginatively known as Sierra One, Two, Three and Four by our UN hosts.

Serbian Army Checkpoint. It was pointed out to me later that taking photos like this can potentially get you shot as a spy.

At Sierra One we were stopped but we didn't have to get out. The Serbian soldiers took a quick count of passports and passengers to make sure they tallied up then waved us through.

Sierra Two and Three also waved us past. Fine, we thought, they've radioed ahead and we clear through.

At Sierra Four we were stopped and asked to get out and line up on the roadside.

The Serbian officer in command was a woman who had aged badly but was probably in her late twenties. She spoke reasonable English and was dressed exactly like so many rock chicks at London's nightclubs of the time - bleached blonde permed hair, too much make up, tight leggings and thigh high boots. The only difference was the blue/grey camouflage Serbian Army jacket she wore over the top.

Following her were two or three soldiers in the same camouflage pattern uniforms but without the leggings and thigh boots. They had Kalashnikovs casually slung over their shoulders. She smiled at us. They didn't.

She went up and down the line of us, examining passports, asking general conversational questions and being ever so charming. Her unshaven escorts did not charm us but stayed back, smoking and eyeing us up and down, no doubt with their trigger fingers itching.

She eventually bid us a happy journey. We were keen to get out of there and quickly got back in the Land Rovers.

Back on our way, the British soldiers told us: "She's one we'll be hunting down after the war. She's had plenty of people shot on the side of the road. She wouldn't touch you guys but we didn't want to mention it before the check in case you got freaked out."

From the Serbian lines we drove up to the UN base at Kiseljack in Croatian-Bosnian territory. There, we finally felt a little relief. We were beyond sniper fire, landmines, stray shells and mortar rounds. Kiseljak was nice; it was the first time in two days when there wasn't any gunfire to be heard in the background.

We weren't bothered at all when we were told that our helicopter ride to Split would be a little delayed. They gave us some lunch instead.

The delay, we were told over lunch, was due to one of their two Sea King helicopters undergoing repairs. It turned out that it had been hit yesterday by small arms fire. Nothing serious, they said.

We had been due to go out on that one but instead we'd have to wait for the other to get back from its current mission and be refuelled.

The UN base at Kiseljak. Notice the two Sea King helicopters. The one on the right, partially tarpaulined, is undergoing repairs after being shot at and ours is on the left.

Pretty much everything that everyone had said since we got here had made me think that this whole trip was a quite stupidly dangerous thing to have attempted but this was at least surely the last crazy thing we'd have to do before going home, so with no option we got into the least damaged of the Sea Kings.

Getting into the Sea King, a British Naval officer was handing out life vests but ran out just before me and Alex Dickson.

"Sorry about that," he said. "We haven't got anymore but not to worry. To be honest they're not a lot of help. Most of the trip is over land, if you do get shot down over the lakes, then you've got to get out of the helicopter and swim clear of the rotors before they hit the water. Once the rotors touch down they'll chop up anything floating within their radius. Then you have to inflate your jacket.

"If you panic and inflate it too early inside the copter, you'll float the to top of it, get stuck in the fuselage and sink with it. Then if you've managed to get out and clear the rotors and inflate your life jacket you might have two or maybe three minutes to swim to safety or get rescued before hypothermia will set in.

"Bearing in mind that the rescue copter is currently under-going repairs, I wouldn't worry about the life jacket too much."

Me in the Sea King helicopter

That was more reassuring advice that made my bowels loosen. But surely, this lot are winding us up a bit with all this scary reassurance? I mean, I know there's a war on but maybe I'm just jumping at shadows and they're all having a laugh at us for it and telling bigger and bigger tales?

Once we were inside the helicopter, they fixed a heavy machine gun to the open port on the right next to us and belted in some ammunition. The gunner cocked it and sat back for the flight. We took off and flew over some stunning forested mountainous countryside.

After the first twenty minutes or so and passing over some lakes, he packed the gun up and put the ammunition away. I asked him why he was packing up now.

"We're past the fighting zone now. We don't need it." More reassurance for now but that meant they really did think there was a possibility of being shot at over the last section: the life-jackets were for real.

But now surely at last the danger really is over. We can rest easy. We're safe and nearly home!

Most of us had headphones on in the helicopter and could hear the pilot and crew talking all the "Roger Charlie Bravo Two Zero" stuff that pilots do. Bruce loves that kind of thing and probably even knew what they were on about.

Bruce on board the Sea King helicopter

Then the pilot said over the headphones: "I hear we have some civvies onboard. We'd like to show you what the Royal Navy can do with a Sea King."

At that moment we dropped out of the sky to below tree level, spun over hilltops at high speed, swung side to side in tight valleys and generally risked our mortality in every conceivable way.

On the ride some of our flight crew shouted: "The Royal Navy are not pussies!!!" I had never suspected they were, and have certainly not doubted it since.

We didn't have seat belts and the starboard side was wide open for the machine gun which had been taken away. We clung on for dear life to anything we could grip.

The flight crew loved it. They must have done it dozens of times before. They threw their heads back and laughed. They lived with mortal risks every day and this was how they dealt with it. More danger, this time for fun.

Other British UN soldiers had told us of similar episodes, for example driving up and down 'Sniper Alley' under fire for kicks or shooting up buildings, which a female UN soldier told us felt "sexy". This is how the human mind deals with being in fear constantly; it turns to viewing the danger as fun.

Black humour was rife in all the UN troops we met. Most of it was good humour with some great jokes and a seemingly fearless attitude. But in some cases I suspected it was caused by intense personal stress with only the comradeship of their unit as a relief.

I've not been on a fair ground ride since. They're all stupid and useless as compared to what the Royal Navy can do with a Sea King.

Andy Veasey, myself and Alex Dickson on board the homebound Hercules. Notice the visible relief on our faces, contrasting with the concerned looks all through the previous two days in Sarajevo.

When we landed at Split we spent an evening drinking with some British special forces (they were highly trained drinkers as well as killers) then flew on a Hercules transporter plane back to RAF Brize Norton where Maiden's legendary roadie, Johnny Allen, picked us up in a splitter van.

"Make sure you've got your seat belts on", he said. It seemed so trivial. We drove at a steady 68 mph down the M40. We were not going to be swerving sniper fire, or being shot down into a frozen lake. Seat belts? Pah!

In fact, of course, wearing a seat belt is a very sensible thing to do back in real life. But that was the problem. British normal life didn't work for me anymore. I'd only been away for a weekend yet everything was changed forever. We'd all changed inside a bit.

I'd not actually been personally shot at, none of us were injured and my family was still alive. I've got nothing to complain about. In fact we got back into London as it was building up for Christmas. Oxford Street, the lights, Santa, presents, shoppers... consumerism. It should be great. But I couldn't be happy.

I tried telling people at home what had happened out there but they couldn't understand. They nodded and agreed but they couldn't see it and I could see that they couldn't see it.

I would break down in tears at the wrong moments, excuse myself and go to the toilet to sort myself out. It's OK. That's a normal reaction. I'm fine now. Mostly. I was only there for a weekend.

But what about the people of Sarajevo? They'd lived through years of it. They actually lost friends, family members and limbs.

What about the soldiers who still fight in Afghanistan and other parts of the world? What happens when they get home after a six month tour of duty?

What about the innocent people who live (and the children who grow up) through that shit in Syria today or any of the many conflict zones around the globe?

Can these people ever be normal again?

Quite frankly no. Seeing a war and its effects and meeting its victims up close for a couple of days was far more shocking than I'd expected. If Tony Blair and George Bush had seen the Bosnian War up close they could never have invaded Iraq.

Living through or taking part in a war is more horrific than can be imagined. You'd literally be scarred for life.

Remember those stories about how Grandad was in the Second World War or Uncle Bob was in Korea and he never wanted to talk about it? He couldn't talk about it.

War veterans walk our streets every day. Their view of the world is very different to ours. Everyday life is extremely trivial to them. The price of tomatoes, someone complaining about a having a headache, soap operas - it means nothing after what they've seen.

But they can't tell you what they've seen because you wouldn't understand it and you would think they are mad, which is what much of society does. They need understanding and support.

In all 18 British soldiers were killed in action in Bosnia, trying to save civilian lives. You can donate towards helping injured British servicemen and women at Help For Heroes by clicking here.

According to the International Center for Transitional Justice, the Yugoslav Wars resulted in the deaths of around 140,000 people in total. Of those over 11,000 were Bosnian civilians living in Sarajevo during the siege and of those over 1,500 were children. A further 15,000 children were injured in Sarajevo.

You can donate to the children of Bosnia at SOS Childrens' Villages by clicking here.

Normal service will be resumed next month. Until then enjoy your life - you are blessed to have it

|

| Roland Hyams and Alex Sponder Elena - smiles all round on the way home |

Thanks to Roland Hyams, Alex Dickson, Alex Sponder Elena, and Mirza Coric for providing extra information about this experience. Thanks very much also to Bruce, Sanctuary Management and Major Martin Morris for making all this possible. However the biggest thanks should go to all the UN personnel who kept us safe, the Serious Road Trip who got us there and the people of Sarajevo who made us feel so welcome throughout.

|

| Sarajevo 2012 |